Tips for hypertrophy specific training to help maximize muscle growth.

Posted by Shaun LaFleur on

Table of Contents

Introduction

If you want to focus solely on building muscle at the fastest rate possible, there are a few things you need to understand that may not be obvious if you're new to lifting or haven't taken a critical look at a lot of the bad information floating around the fitness industry. In this article I will go over some of the most important concepts when it comes to maximizing muscle growth, as well as touch on some of the misconceptions that revolve around this topic, namely the differences between training for strength and training for muscle growth. Believe it or not, there is a difference and when training to maximize one, the other will suffer.

Properly tracking volume, and volume recommendations

One of the foundations of any good routine is training volume. So it's important to start off by understanding training volume and how to properly apply it to your training. The two most common methods of defining training volume are "volume load", which is simply Sets x Reps x Weight, and "total hard sets", which is calculated by counting how many "hard sets" you perform, with a "hard set" being defined as a set that leaves no more than 4 reps left in the tank. Both definitions have their pros and cons and can be used to track volume when you train, however, "total hard sets" seems to be the more practical way of tracking volume for muscle building goals, and we'll explain why.

In our article [The Truth About Rep Ranges] we discuss how all rep ranges build roughly the same amount of muscle as long as you take each set near failure. Additionally, the more sets you perform in any rep range, the more muscle you will build, regardless of volume load (sets x reps x load). In other words, when comparing training sessions, the session that has more total hard sets will produce more hypertrophy, regardless of the load or rep ranges used, even if the session with less total sets equates to a higher volume load when calculating.

This means that tracking volume in traditional terms of "volume load", which is defined as Sets x Reps x Weight, may not be the most practical way to track volume for hypertrophy specific goals, since it isn't as closely correlated to muscle growth as total hard sets. A more modern and practical approach to tracking total volume for hypertrophy, then, is to track how many hard sets you perform.

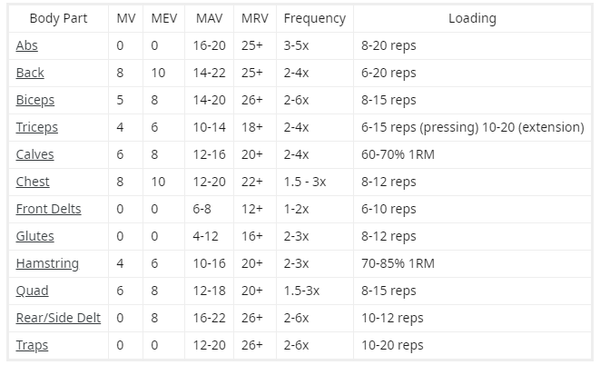

A baseline recommendation for volume requirements for hypertrophy is to train a muscle with a minimum of 10 sets per week. There are definitely benefits to going higher than this, but eventually you will run into diminishing returns once you increase sets past a certain point. Additionally, if you perform too much volume, you can actually slow down progress or even regress due to difficulties recovering. Below is an image derived from volume recommendations from Mike Israetel. This is simply a rough estimate and individual needs will vary widely. For definitions of each label, read below the image.

MV = Maintenance Volume. The amount of volume needed to maintain a muscle.

MEV = Minimally Effective Volume. The minimal amount of volume needed to grow a muscle.

MAV = Maximum Adaptable Volume. The sweet spot; the most volume that your muscle can respond and adapt to. Thought to be more of a range rather than set amount.

MRV = Maximum Recoverable Volume. The most volume you can do and still recover from.

A good strategy is to start out with a base of 10 sets per muscle per week, then slowly increase the amount of sets you're doing each week. Do this until you feel as though you're reaching a point where the volume levels being performed are starting to cause recovery problems or are simply unsustainable from a practicality stand point (spending too long in the gym for example). This will give you a better understanding of how much volume each muscle group can handle.

An example of how to do this would be to first find your base level of volume that you can easily perform consistently. Then, over a period of weeks, slowly increase the amount of sets you're doing until you feel as though you're reaching a point where it is hard to recover consistently. After hitting this point, you can either 1) back off on the volume a small amount and maintain a level of volume that is somewhere between your starting base level and the amount of volume you find difficult, and then progress via adding load and reps when possible or 2) take a deload after hitting this high level of volume that is hard to sustain, reset your volume levels back to baseline, add weight and/or reps to each exercise and then continue to increase sets again.

Here is a quick example of the second, ramping approach:

- Week 1: 3x6 Bench Press @ 200 lbs

- Week 2: 4x6 Bench Press @ 200 lbs

- Week 3: 5x6 Bench Press @ 200 lbs

- Week 4: 3x6 Bench Press @ 205 lbs

- repeat..

Train with enough frequency to perform adequate volume.

In our article [Training Frequency: How often should you train?], we discuss how research shows that training a muscle more than once per week is ideal, with anything over two times a week providing very slight increases in hypertrophy, but with diminishing returns as frequency increases.

This means you should consider training a muscle 2-3 times per week so that you not only optimize hypertrophy, but make it much easier to increase volume levels without your workouts becoming excessively long. The more frequently you train a muscle, the easier it is to perform more total sets for that muscle group. Trying to jam a ton of volume into a single workout instead of spreading it across multiple workouts can lead to multiple problems.

Imagine that you aim to train your chest with 20 sets this week. If you only work out your chest once a week, you'd have to perform 20 sets in that one workout. Not very practical, and if you do manage to do it, odds are that your latter sets during that workout will produce sub par stimulation because of poor performance brought on by fatigue. Training two or three times a week, however, makes getting these 20 weekly sets in much easier. Each session would only require you to perform 10 sets for twice a week frequency or 6-7 per session for three times a week - much more manageable!

Managing volume levels with muscle prioritization

Without going into too much detail, there are two major types of training fatigue - there is local muscle fatigue and systemic fatigue (think overall, general fatigue). All exercises will cause both types of fatigue. The closer you train a muscle to it's MRV (the concept of Maximum Recoverable Volume mentioned previously), the more training fatigue you will accumulate due to the higher overall volume levels. When doing this on multiple exercises, systemic fatigue can rise rather quickly. This means that you can't simply train every muscle near their MRVs at the same time without running into recovery issues.

If you attempted to train every single muscle with volume levels near their MRVs, you'd quickly dig yourself into a recovery hole and be unable to properly recover between workouts, thus lowering your long term ability to build muscle. This is because not only does each individual muscle have an MRV, but your body as a whole can only handle so much systemic fatigue. In other words, you simply CAN'T consistently recover from training every single muscle group at or near their MRVs at the same time.

To alleviate this problem, you need to prioritize muscle groups in each training cycle. I'd recommend choosing 1-3 muscle groups that you want to grow maximally, and train those muscles near their MRVs, while every other muscle can be trained with slightly less volume that is further away from their MRVs, but still enough to grow at a decent pace. For some strong points you have, you may even be okay with training those muscles at only their maintenance volumes to allow yourself more room to push other muscle groups closer to their MRVs.

Choose exercises with a good SFR

SFR stands for Stimulus to Fatigue Ratio, a term coined by [Mike Israetel]. SFR refers to the ratio in which an exercise produces hypertrophy adaptations versus how much fatigue it generates. Some exercises such as the deadlift will generally have bad SFR for most lifters, while other exercises will have very different SFRs between individuals. This means that each individual should test many different variations of exercises to discover which exercises provide the best SFR for themselves.

An example of an exercise with a bad SFR for an individual would be someone who performs the bench press with the intention of building bigger pec muscles, but they don't ever feel fatigue in their pecks after doing bench press. This would mean that despite the bench press being a very good and popular movement, for the sole purpose of growing this particular lifter's pecs, it may not have the best SFR, because the bench press in their case would generate more overall fatigue than it does pec hypertrophy.

Another thing to look for in terms of fatigue generation is just overall discomfort. If a movement gives you aches or pains when you do it a lot, you may want to consider different movements that stimulate the same muscles without the additional wear and tear. Sometimes making very small variations to a movement, such as changing grip width, can have drastic results on SFR.

Put strength on the back burner

While there is nothing wrong with expecting and looking forward to making strength gains, you should put strength training specific workouts on the back burner. Avoid training in rep ranges lower than 5-6 reps and avoid exercises that are more stimulative to strength than hypertrophy (deadlifts for example). While most rep ranges build similar amounts of muscle, training very heavy produces much more fatigue and will therefore have a very poor SFR for hypertrophy. On top of this, because of the increased fatigue that very low rep ranges cause, it will hinder your ability to perform a lot of volume, directly impacting how much muscle you can build.

It's a common misconception that you have to get stronger in order to build muscle. It's actually quite the opposite. Getting stronger is a side effect of your muscles growing (as well as many other things that are beyond the scope of this article), not the other way around. While you don't need to get stronger in order to get bigger, getting stronger can be a great sign that you're building muscle. Naturally, you will still need to add load to the bar over time in order to maintain the correct proximity to failure (remember, you must train close to failure to produce adequate growth stimulus) as you get stronger. This is likely what causes confusion and people to think that it is the act of adding load that builds muscle.

Another tip is not to obsess over the "big 3" (Bench, Squat & Deadlift) like many lifters do. These movements, while great, are not requirements for hypertrophy training, especially if they don't have a good SFR for you personally. The deadlift, for example, is often one of the most commonly left out compound movements for hypertrophy specific routines because it has such a bad SFR for most lifters.

Avoid using momentum and cheating on exercises

For hypertrophy training, the goal of any exercise is to specifically target a muscle or muscle groups and work them until they're near their limits. It's not to lift a certain amount of weight for a certain amount of repetitions. You simply need to take the muscle close to its limits regardless of how much weight or reps it takes. It's common for lifters to have a certain amount of reps in mind when starting a set, and they'll often use bad practices to stick to that amount of reps, be it stopping a set TOO early because they've hit their target or using momentum because they know they can't reach their rep goal using solid form. Using momentum can take an exercise with great SFR and turn it into a movement with terrible SFR.

Take a bicep curl for example. Often times people become obsessed with their strength on an exercise and want to lift a certain weight on the bar or they want to hit a certain number of reps, so instead of focusing on strictly moving through the range of motion in order to stimulate their biceps, they begin swinging their body and using momentum just for the sake of saying they were able to lift x amount of weight or perform y amount of repetitions. When this happens, they no longer stimulate the biceps nearly as much and their biceps growth will suffer. After all, your biceps don't care how much weight you can lift or how many reps you can perform - if you don't take them near their limits, they have no reason to adapt and grow.

When you start bringing momentum into exercises, you take the focus off of the muscles that the movement was intended to target, shift the focus onto other muscles, and worst of all, increases your chance of injury. You are essentially wasting time and putting yourself at a higher risk of having to take time off from getting hurt.

Thank you so much, this is a great article with a lot of important knowledge for lots of lifters